By: Dr. Geoffrey Lossie

Edited by: Dr. Pat Wakenell

Abstract

Coccidiosis is a protozoal disease of the intestines (or kidneys in geese) caused primarily by parasites in the genus Eimeria. There are nine described species of Eimeria in chickens and seven in turkeys, but not all of the species are capable of causing disease. It is important to note that coccidia is species specific, meaning that chicken coccidia do not affect turkeys and vice versa. The coccidial life cycle is complex but direct, with infection occurring via fecal-oral transmission. Oocysts (similar to an egg) are shed directly in the feces where they can contaminate feed, water, litter, and soil. Fresh oocysts are not infective until they incubate in the environment for 1-2 days and become sporulated at the proper temperature, moisture, and oxygen levels1. Mechanical and biological vectors are important as well. Mice and flies can transport infective oocysts during their normal feeding habits, while other insects such as darkling beetles can ingest the oocysts which can remain infective until the darkling beetle is consumed by a chicken. The most common means of spread, however, is via movement of personnel between pens, houses, or farms that are harboring oocysts on their clothes or boots5. Once oocysts are ingested an asexual and a sexual life cycle are completed that ends with the production of new oocysts that are excreted in the feces. The whole cycle from ingestion to the release of new viable oocysts is 4-6 days3. Lesions in the gut are produced by destruction of the epithelial cells via development, multiplication, and release of various life cycle stages from the epithelial cells3. Damage from the continuation of the coccidia life cycle leads to diarrhea, dehydration, weight loss, rectal prolapse and death8. Prevention of coccidiosis is key. Backyard flock owners should routinely clean out their coops/yards to reduce environmental oocyst numbers. Keeping an appropriate density of poultry, feeding commercial feeds that contain amprolium, and soaking the soil with dilute bleach and rototilling on a monthly basis are great ways to prevent outbreaks. A representative fecal sample from the flock should be tested once or twice a year. Amprolium, dosed via the drinking water, is the medication of choice for coccidia with treatment lasting for 5-7 days unless the case is complicated.

Figure 1: Two backyard chickens with coccidiosis in a repurposed swine barn. There are multiple piles of loose stool. Both birds were listless with a hunched posture. This image illustrates the necessity of having appropriate litter that can be regularly cleaned. Photo courtesy of Dr. Pat Wakenell.

Figure 2: Small mobile chicken coop housing numerous birds. In the winter this coop was used to house the birds in the image. This amount of space was inadequate, and the birds developed clinical coccidiosis. Photo courtesy of Dr. Pat Wakenell.

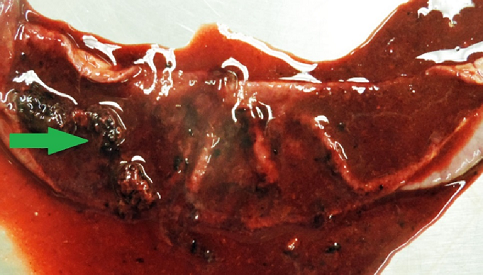

Figure 3: Section of small intestine from a chicken infected with E. necatrix. The lumen is full of frank blood with flecks of clotted blood. Note the necrotic, hemorrhagic, debris within the lumen (green arrow).

Complete article:

CoccidiaLossey.pdf