|

Search

|

|

|

Laboratory Diagnosis of Bovine Abortion

|

|

| Middle-trimester Holstein fetus. Note the amniotic plaques that are prominent at this gestational stage. Because the bovine fetus seldom has diagnostic gross lesions, histologic and ancillary testing on fetal and placental tissues is integral to determining the cause for abortion. |

|

Fetal

loss has a major impact on the dairy and beef industries. An estimated 6-10%

of pregnancies terminate in abortion, stillbirth or perinatal death at a

projected cost up to $900 per case.

Diagnosticians at the Indiana Animal Disease Diagnostic

Laboratory (ADDL) and the Heeke ADDL at the Southern Indiana Purdue Agric-ultural

Center (SIPAC) are cooperating in a project to monitor bovine fetal loss in

Indiana and to improve diagnostic success in cases of abortion or perinatal

death. We hope to increase the number and quality of case submissions, improve

ancillary |

methods to identify infectious agents, and correlate pathologic

findings with ancillary test results for meaningful and accurate diagnosis.

Prompt submission of the entire fetus with placenta in every a

bortion case is

ideal. When this is impossible or impractical, please contact the Purdue ADDL

or Heeke ADDL at SIPAC to discuss specimen selection and submission. Necropsy

in abortion cases is performed according to a standard procedure. Macroscopic

examination is used to detect malformations or gross lesions. Selected

formalin-fixed tissues (placenta, brain, heart, lung, liver, kidney, spleen,

digestive tract, and skeletal muscle) are examined histologically to detect

microorganisms, specific lesions, or inflammation as a clue to infectious

disease, or degenerative changes that might incriminate a toxic or nutritional

disease. Ancillary tests are applied as indicated by history or lesions.

Microbiologic tests are applied as routine abortion screens for those cases in

which neither the history nor pathologic examination incriminates a specific

cause. Placenta, lung, liver and abomasal content are appropriate specimens

for bacterial culture; for virologic testing, placenta, lung and spleen. Fetal

pericardial or thoracic fluid can be evaluated serologically to detect

antibodies to known abortifacient agents. Selenium concentrations can be

measured in fetal liver. |

|

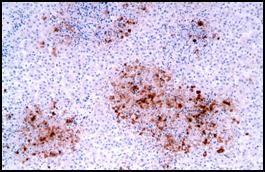

| Photomicrograph (courtesy of Dr. Ramos) from a case of

IBR abortion. Necrotic foci in this fetal liver are highlighted by immunohistochemistry for bovine herpesvirus 1. |

|

In 2008,

an infectious cause was suspected in 21 of 47 cases of bovine abortion,

stillbirth, or perinatal death that were examined by necropsy. Twelve of these

cases were attributed to various bacterial pathogens; 6 were considered viral

abortions; 3 cases were attributed to Neosporum caninum. Four of the

six viral abortions were diagnosed as Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR); immunohistochemistry

provides an excellent means to detect IBR herpesviral antigen within the

necrotic foci that are

the diagnostic lesion in this disease. |

Twinning and dystocia were

noninfectious factors that contributed to

several perinatal deaths. Disappointingly,

no cause for abortion,

stillbirth, or perinatal death was determined in 17 cases (36%). Incomplete

submission (particularly omission of the placenta) and post mortem

decomposition of the fetus may account for failure to determine the cause for

abortion or stillbirth in many cases.

In cases of bovine abortion, stillbirth or perinatal death, rapid and accurate

diagnosis is essential for management and reduction of fetal loss. Continued

surveillance and improved diagnostic testing are our goals. The ADDL and Heeke

ADDL at SIPAC hope to increase diagnostic success in bovine abortion cases by

increasing the number and quality of submissions.

Please try to deliver the entire fetus with placenta to the diagnostic

laboratory in each case of bovine abortion.

-by

Dr. Peg Miller, ADDL Pathologist

References:

-

Anderson ML, 2007: Infectious causes of bovine abortion during mid- to

late-gestation. Theriogenology 68: 474-486.

-

Buxton D, McAllister MM, Dubey JP, 2002: The comparative pathogenesis of

neosporosis. Trends Parasitol 18: 546-52.

-

Grooms DL, 2004: Reproductive consequences of infection with bovine viral

diarrhea virus. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 20:5-19.

|

|

|

|

|