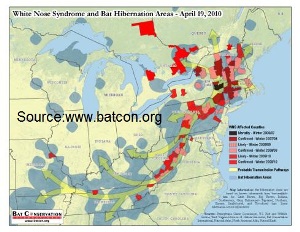

In February 2006, White-nose Syndrome (WNS) was first documented at Howe’s Cave, New York. White-nose syndrome is a lethal dermatophytic disease of hibernating bats associated with Geomyces destructans sp. nov. As of March, 2010, WNS has been confirmed in caves and mines throughout the eastern United States, including Alabama, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia. More than a million bats of six different species have perished from this deadly disease with mortality rates approaching 100% at many sites. In March, biologists in Ontario reported the first detected case of WNS in Canada. White-nose syndrome continues to spread rapidly across North America, seriously threatening the remaining colonies of hibernating bats.

Geomyces destructans is a novel Geomyces fungal species. Geomyces sp. are slow-growing, opportunistic fungi found primarily in the soil of colder regions worldwide. The fungus produces hyphae and arthroconidia. Unlike conidia of other species, Geomyces destructans are asymmetrically curved. Optimal growth of G. destructans occurs at temperatures found in winter bat hibernacula. The body temperature of bats in torpor (temporary hibernation) drops to within a few degrees of the ambient temperature of their hibernaculum, usually 36° to 50°F. During torpor, the bat’s metabolic rate drops by approximately 96% and the immune response is down-regulated, providing ideal conditions for growth of G. destructans.

The primary route of transmission of WNS is bat to bat contact with fungal spores. Fungal spores of G. destructans originated from European caves. These spores were inadvertently spread to caves and mines in the United States by fomites, the contaminated equipment and clothing of cavers.

The classical presentation of WNS in hibernating bats includes profuse white delicate hyphae and conidia covering the surface of the muzzle, wing membranes and/or the pinnae. Animals suffering from WNS emerge prematurely from their hibernaculum, are emaciated with depletion of fat reserves, and wings are damaged or scarred due to fungal invasion.

Visible fungus on the skin of bats is often not observed once the bat emerges from the hibernaculum making gross disease difficult to detect. Definitive diagnosis of WNS requires histopathology with preferred tissue samples from the rostral muzzle, nose and wing membrane.

Histologically, affected tissues have extensive fungal invasion of the dermis with an absence of inflammatory response. The diameter and shape of hyphae vary. Hyphae can have parallel or non-parallel walls measuring 2-5μm. Curve-shaped conidia measuring 2.5μm wide and 7.5 μm in length have uni- or bi-lateral blunted ends, and a basophilic center. Fungal hyphae fill hair follicles and sebaceous and aprocrine glands of the muzzle with invasion of underlying tissues. In the wing membrane and pinna, fungal hyphae are associated with epidermal erosions and ulcers which extend into underlying connective tissue. Bats collected shortly after hibernation also have small quiescent packets of fungal hyphae within the dermis surrounded by a thin layer of acellular material.

Currently, surveillance of White-nose Syndrome is being conducted by the United States Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center (Madison, WI) and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service with the collaboration of State wildlife specialists and biologists.

Federal agencies recommend adherence to cave advisories and closures to help prevent the transmission of WNS. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services outline decontamination protocols to be used before entering a cave. Updated protocols can be found at www.fws.gov. Protocols for bat submission can be found at www.nwhc.usgs.gov. For the most current information on White-nose Syndrome, visit the websites of the United States Geological survey National Wildlife Health Center at www.nwhc.usgs.gov or Bat Conservation International at www.batcon.org/wns.

-by Hillary Hart, Clinical Year Student

-edited by Dr. Abby Durkes, ADDL Graduate Student

References

- Bat Conservation International www.batcon.org/wns

- Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr MJ et al: 2009. Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science 232:227.

- Carey HV, Andrews MT, Martin SL: 2003. Mammalian hibernation: cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol Rev 83:1153-1181.

- Clawson RL, Missouri Department of Conservation. www.mdc.mo.gov

- Gargas A, Trest MT, Christensen M, Volk TJ, Blehert DS: 2009. Geomyces destructans sp. nov. associated with bat white-nose syndrome. Mycotaxon 108: 147-154.

- United States Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center www.nwhc.usgs.gov

- Uphoff Meteyer C, Buckles EL, Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Green DE, Shearn-Bochsler V, Thomas NJ, Gargas A, Behr MJ: 2009. Histopathologic criteria to confirm white-nose syndrome in bats. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 21:411-414.