|

Search

|

|

|

|

Bovine tuberculosis is an important infectious disease

worldwide that threatens the lives and livelihood of those people associated

with the cattle industry. Many countries, including the United States, are trying to identify and prevent the spread of this disease through testing and eradication

programs. Bovine tuberculosis is a zoonotic disease that causes respiratory

disease in both cattle and humans. The organism can be transmitted to humans

through infected unpasteurized milk or the inhalation of bacteria at the time

of slaughter..

Bovine tuberculosis is spread through aerosolized droplets

or ingestion once it is established in a herd of cattle. The incubation period

can range from months to years with the severity depending on the immune system

of each individual animal. Infection results in chronic disease; animals

typically present with clinical signs during times of increased stress or as

they age. The organs that can be affected include the lungs, liver, spleen,

lymph nodes and intestines. The clinical signs include moist cough, dyspnea,

weight loss, anorexia, lymphadenopathy and diarrhea. |

|

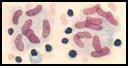

Mycobacterium bovis is the organism that

causes bovine tuberculosis. The bacteria are acid fast,

filamentous, curved rods. The bacteria usually enter the respiratory system of

a cow and settle in the lungs. Macrophages in lungs are then responsible for

phagocytizing the organism. |

The organism replicates intracellularly after it

has been taken up by the macrophages. A granuloma or tubercle forms as the

body tries to wall off the infected macrophages with fibrous tissue. The

granuloma is usually 1-3 cm in diameter, yellow or gray, round and firm. On

cut section, the core of the granuloma consists of dry yellow, caseous, or

necrotic cellular debris. The infection can spread hematogenously to lymph

nodes and other areas of the body and cause smaller, 2-3 mm in diameter,

tubercles. The formation of these smaller tubercles is known as “miliary

tuberculosis”. The histological lesions consist of necrotic cells in the

center of the tubercle surrounded by epitheloid cells and multinucleated giant

cells all encapsulated by collagenous connective tissue. The necrotic core of

cells can often become calcified as the tubercle matures.

Diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis can be accomplished through

gross examination, histology, acid-fast staining, culturing the bacteria, and

PCR. In the live animal, interferon gamma testing, enzyme linked immunosorbent

assay (ELISA) testing, and tuberculin testing can be performed. The interferon

gamma test is a whole blood immunoassay that detects the presence of the

cytokine produced by natural killer cells in response to mycobacterial

protein. However, the most common in vitro test used in the United States is the tuberculin skin test.

Tuberculin skin testing is based on T-cell response to

mycobacterial proteins. The caudal-fold tuberculin test is performed using

0.10 cc of a purified protein derivative. This is injected intradermally in

the skin of the tail. The injection site should be examined for a reaction 72

hours post inoculation. If there is a reaction, such as a discolored raised

area, the animal is classified as a responder and undergoes a comparative

cervical tuberculin test. The test is more sensitive and helps to determine

whether the animal is infected with M. bovis as opposed to M. avium or M. paratuberculosis. This test is performed by injecting 0.10 cc of

a more potent purified protein derivative intradermally into the cervical

skin. If the animal responds to this injection, it is classified as a reactor;

the animal will be euthanized and a necropsy should be performed to determine

the extent of the infection.

Currently, treatment of bovine tuberculosis is not

recommended due to its infectious nature. If an animal is found to be infected,

it should be culled from the herd. However, there are some preventative

measures available. One way to ensure that cattle do not become infected is to

eliminate any possible interaction with deer. A population of white-tailed

deer was found to harbor Mycobacterium bovis in lower Michigan in

1995. White-tailed deer can be infected with tuberculosis infection and spread

it to uninfected cattle through nose to nose contact, aerosol droplets, or

indirect contact. The indirect contact is usually a result of cattle ingesting

feed that has been contaminated by deer saliva. It is recommended that any

feed for cattle be protected and stored away from deer. Other programs to

control the deer population, such as hunting and banning feeding, have been implemented

to decrease the density of deer and the population of affected deer.

Vaccination for the prevention of bovine tuberculosis is

another option that is being investigated. A vaccine was created for M.

bovis in the 1920s by Calmette and Guerin. The BCG vaccine has undergone

some scrutiny due to variable efficacy. The vaccine reduces the severity of

the disease, usually allowing the bacteria to infect only a few lymph nodes,

but does not prevent infection. The vaccine can also cause false-positive

caudal fold skin tests, which can cause confusion when testing is performed.

There are studies researching the efficacy of combining the BCG vaccine with

mycobacterium protein and DNA. The goal is to develop an enhanced vaccine that

can provide protection against the disease. The vaccine would be given to

wildlife in an effort to prevent the spread of the disease to cattle.

Bovine tuberculosis poses a significant risk to human and

herd health. The only way to be protected from the disease is through

prevention. It is important to limit the exposure of the herd to other

infected cattle or wildlife. Testing and eradication of infected animals is

the current method of control, though additional research is currently being

explored in the areas of vaccinations and other possible preventative measures.

-by Rose Paylor, Michigan State University Veterinary Student

-edited by Dr. Pam Mouser, ADDL Graduate Student

References:

-

Buddle BM, Wedlock DN, Denis M: 2006. Progress in the

development of tuberculosis vaccines for cattle and wildlife. Vet Microbiol

112(2-4): 313-323.

-

Cagiola M., Feliziana F, Severi G, et al: 2004.

Analysis of possible factors affecting the specificity of the gamma interferon

test in tuberculosis-free cattle herds. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11(5): 952-956

-

Jones TC, King NW, Hung R: 1997. Veterinary Pathology,

6th ed., Williams and Wilkins. Baltimore MD. P 490.

-

McGavin MD, Carlton WW, Zachary JF: 2001. Thomson's

Special Veterinary Pathology, 3rd ed. Mosby Inc., St. Louis MO. Pp 170-1.

-

Miller JM, Jenny AL, Payeur JB: 2002. Polymerase chain

reaction detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and Mycobacterium

avium organisms in formalin-fixed tissues from culture-negative ruminants.

Vet Microbiol 87(1): 15-23.

-

Norby B, Bartlett PC, Fitzgerald SD et al: 2004. The

sensitivity of gross necropsy, caudal fold and comparative cervical tests for the

diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis. J Vet Diag Invest 16(2): 126-131

-

O"Brien DJ, Schmitt SM, Fitzgerald SD, et al: 2006.

Managing the wildlife reservoir of Mycobacterium bovis: The Michigan, USA, experience. Vet Microbiol 112(2-4): 313-323.

-

O'Brien DJ, Schmitt SM, Fierke JS et al: 2002.

Epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis in free-ranging white-tailed deer. Michigan, USA 1995-2000. Prev Vet Med 54(1): 47-63.

-

Palmer MV, Waters WR, Whipple DL: 2004. Investigation

of the transmission of Mycobacterium bovis from deer to cattle through

indirect contact. Am J Vet Res 65(11): 1483-9.

-

Pollock JM, Rodgers JD, Welsh MD, McNair J: 2006.

Pathogenesis of bovine tuberculosis:

-

Thoen C, LoBue P, DeKantor I: 2006. The importance of Mycobacterium

bovis as a zoonosis. Vet Microbiol 112 (2-4): 339-345.

-

The role of experimental models of infection. Vet Microbiol

112(2-4): 141-150.

-

www.michigan.gov/emergingdiseases

|

|

|

|

|